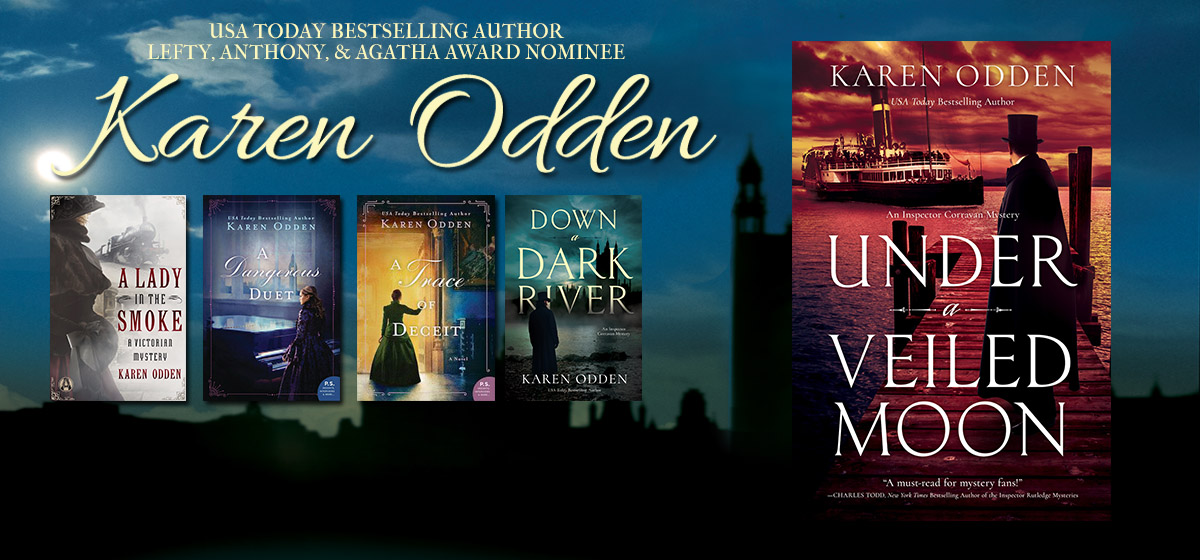

So two months ago, I finished a draft for my next novel, DOWN A DARK RIVER, about an inspector at Scotland Yard named Michael Corravan. It is set in the spring of 1878, mere months after a bribery and fraud scandal has put three Senior Inspectors in jail, and the Yard is viewed with suspicion by the press and the public alike. One morning, a murdered young woman, the daughter of a wealthy judge in Mayfair, is found floating down the Thames in a lighter boat.

I sent it to my agent Josh, who said: “It’s amazing! I love it! The history, the suspense, the inspector! But, Karen, it’s 136,000 words long!” This genre of police procedural, he explained, usually runs about 100K—and if it’s historical, you can get a way with a little longer.

I know I tend to overwrite that first draft; I “write my way in” to a book and have to chop out the first chapter or two. Or seven. (As in the case of my first novel.) Much of that is back story, which is necessary to keep in my brain, but not necessary to keep in the manuscript. The comments about my first novel, A LADY IN THE SMOKE, included that it was well written but at times a bit slow, a bit wordy. So I believed him. I promised to do what I could and hung up the phone.

36,000 words? One-quarter of the book?! It’s like going on an all-lettuce diet. Painful.

Among the many lessons I learned from my first book was the value of giving it to readers who come cold to a manuscript. So I reached out. Six people agreed to read the book: a friend who has published four books and has her fifth coming out; a professor of Victorian literature; two friends who read widely across every genre; my sister, who is a former humanities teacher and likes to scribble in margins; and a museum curator/archivist in California who was incredibly supportive of LADY. All of them asked me what kind of feedback would be most helpful, so I wrote a cover letter, which for most included this paragraph:

Dear Reader (just like in Jane Eyre): The kindest and most helpful comment you can make is, I’m getting bored. Because if you are, a potential editor definitely will be. Tell me where your mind wanders because that’s where my cuts will begin. Tell me any time your brain “stops” you and pulls you out of the story. You can just make a quick note: “She wouldn’t say this.” “Why is he angry?” “Feels too modern.” “Wait, didn’t he say he was 19 before?” “Who’s this character? Can’t remember.” “This feels like an info dump.” “You’ve used this word three times in a row.” That is usually all I need to take a closer, directed look at a particular passage.

People took varying lengths of time—from three days to three weeks—and provided feedback in various ways: one called me to talk; one typed up pages of notes; three used the “insert comment” function; one scribbled on hard copy. My author friend completely agreed with my agent; shorter is easier to sell and appropriate to the genre, she insisted, pointing to dialogs in particular that could be cut by half. The professor suggested other cuts and pointed out that the word “lapin” in French is actually “rabbit” not “wolf.” (Arg. I know that. So how did I read over that passage a dozen times and not catch it?) My sister and reader friends pointed out dozens of inconsistencies in character, typos, grammar mistakes, and subplots that didn’t seem to go anywhere and could be nixed. The curator/archivist pushed me to think hard about the relationships between the characters: Why are James Everett (the doctor) and my inspector even friends, when they’re so different? And how deeply does the inspector love Belinda, and why doesn’t she appear until chapter 14?

Six weeks later, I have a manuscript that is considerably leaner … 106,000 words and so very much better because of my readers, including these six and others, who have read my first pages and scraps. In my gratitude journal (which I try to keep daily) my beta-readers are 1, 2, and 3 today.